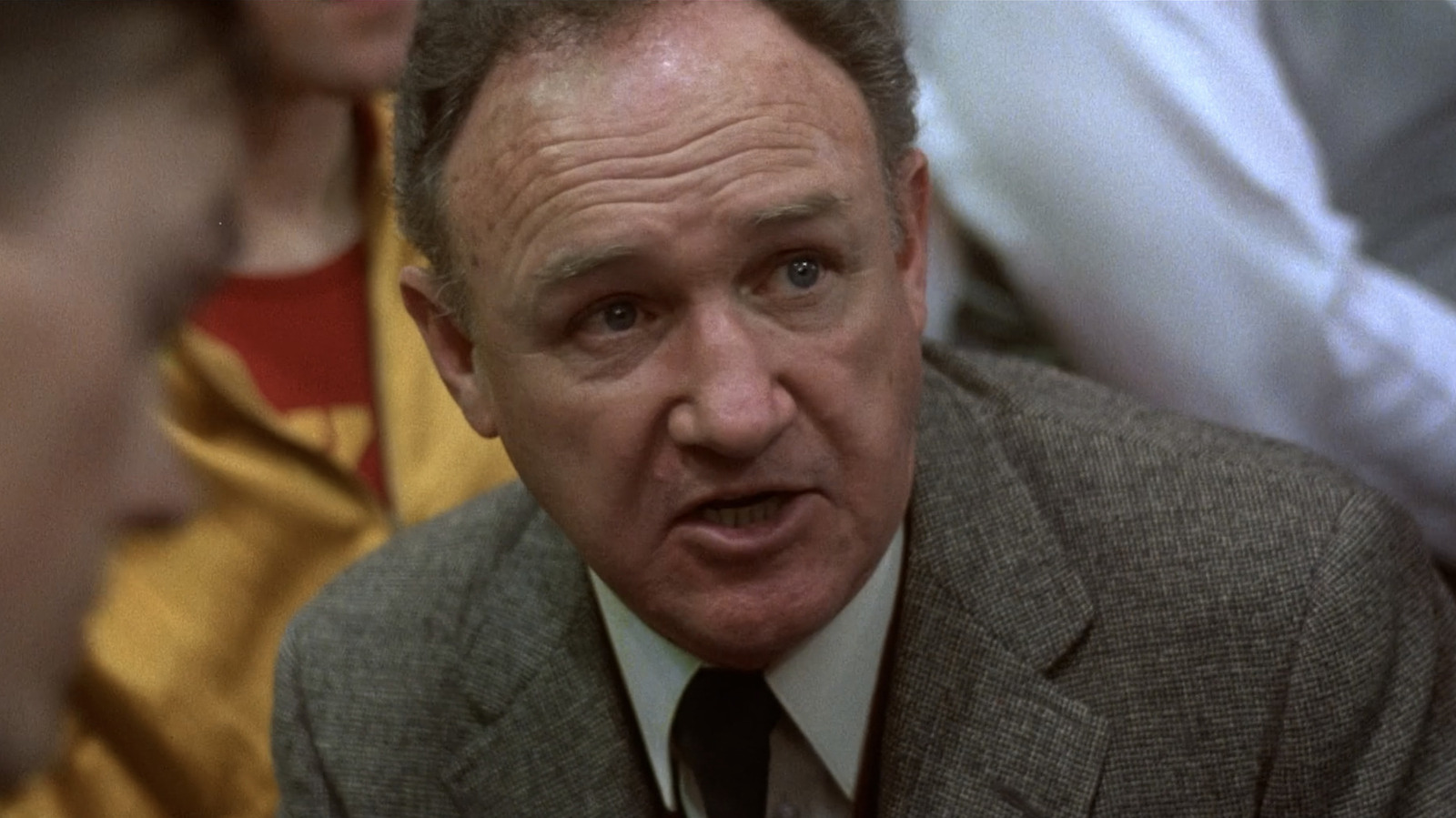

Chi Chi Rodriguez, whose flamboyance on the course and passion for the game of golf transformed him into one of its most popular players through his more than three decades on the pro tours, died on Thursday. He was 88.

His death was announced by the PGA Tour. The announcement did not cite a cause or say where he died.

In a sport typically associated with lush country clubs where respectful crowds idolize often bland players with comfortable roots, Rodriguez broke the mold.

Growing up in a poor family in Puerto Rico, he almost died at age 4 from vitamin deficiencies. At 7, he helped out in the sugar cane fields where his father, Juan Rodriguez Sr., whacked away with a machete for a few dollars a day.

The boy who would be known as Chi Chi also began caddying at a course that drew affluent tourists. He taught himself to play using limbs from guava trees to propel crushed tin cans into holes that he had dug on baseball fields, and when he was 12 he shot a 67 in a real game of golf. After playing in Puerto Rican tournaments, he joined the PGA Tour in 1960.

Rodriguez was 5-foot-7 and about 120 pounds. But he used his strong hands and wrists to get off long low drives, and he was an outstanding wedge player, offsetting his sometimes balky putting game. “For a little man, he sure can hit it,” Jack Nicklaus told Sports Illustrated in 1964, relating how Rodriguez often outdistanced him off the tee on flat, into-the-wind fairways.

Rodriguez won eight tournaments on the PGA Tour, then became one of the top players on the Senior (now Champions) Tour, capturing 22 events, including two majors: the 1986 Senior Players Championship and the 1987 Senior PGA Championship. He was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1992.

And he played with a flourish seldom seen.

When he made a birdie, he would cover the hole with his narrow-brim straw hat, then perform a toreador dance.

“One morning we were playing for five cents a hole,” he once told People magazine, recalling his long-ago games against fellow caddies. “I made a 40-foot putt, but there was a toad in the hole. When he hopped out, the ball came with it. I lost the nickel.” That inspired him to make sure that his ball would never again escape prematurely — or so the tale went.

After draining a difficult putt, Rodriguez would sometimes turn his putter into a simulated sword being unleashed on a bull, then wipe imaginary blood from it and place it in an invisible scabbard.

Such theatricality, plus his chattering with the galleries, didn’t endear him to some of his playing partners.

He was fined $200 by the P.G.A. in October 1970 after Dave Hill complained that Rodriguez had distracted him during the Kaiser Open in California when he sought to amuse spectators with a simulated attempt to bat a golf ball with a bunker rake.

Rodriguez always maintained that he meant no disrespect to the game. But, as he once put it: “Golf is show business. I love to make people laugh.”

For all his success, Rodriguez never forgot his origins, having been inspired to help others by his father’s generosity to those who had even less than him.

After visiting a Florida juvenile detention center to give a golf clinic, he vowed to do more. In 1979, he became a founder of the Chi Chi Rodriguez Youth Foundation, which provides counseling, educational and vocational training for disadvantaged students, and he contributed substantially to its funding. The Clearwater complex, in Clearwater, Fla., now includes a public-private academy for students from the fourth to eighth grades.

“I love kids because I never was a kid,” Rodriguez once said. “I was too poor to be a kid.”

Juan Antonio Rodriguez Jr. was born on Oct. 23, 1935, in Rio Piedras, P.R., one of six children. Beyond golf, he played baseball as a young man and called himself Chi Chi after the Puerto Rican professional baseball player Chi Chi Flores.

He served in the Army in the mid-1950s and then became the assistant pro at the Dorado Beach Resort in Puerto Rico, outside San Juan. He received a $12,000 stake from Laurance S. Rockefeller, who developed the property, to help finance Rodriguez’s beginnings on the PGA Tour. His eight victories included the 1964 Western Open and the 1972 Byron Nelson Classic.

Rodriguez joined the Senior Tour in 1985 and became one of its top money winners, crediting the teaching pro Bob Toski with improving his game. “Bob told me to stand taller,” he said. “At least, as tall as someone like me can stand. It helped my swing and it helped my putting.”

In his later years he lived at the El Legado Golf Resort, which he built, in Guayama, on the island’s south coast. In May 2010, masked nighttime intruders tied him up along with his wife, Iwalani, and robbed them of cash and jewels valued at $500,000.

Rodriguez is survived by a daughter, Donnette Markham; two brothers, Jesus and Julio; and three sisters, Juanita, Carmen and Maria. His wife, a native of Hawaii, died in 2021.

Rodriguez complemented his flair on the golf course with a host of wry observations, often at his own expense.

On his youth: “I was poor when I was starting out. I mean, I had a room so small I couldn’t even change my mind.”

On his persona: “I’m a hot dog pro. That’s when someone in the gallery looks at his pairing sheet and says, ‘Here comes Joe Baloney, Sam Sausage and Chi Chi Rodriguez. Let’s go get a hot dog.’”

On his putting problems: “I read the greens in Spanish, but I putt in English.”